|

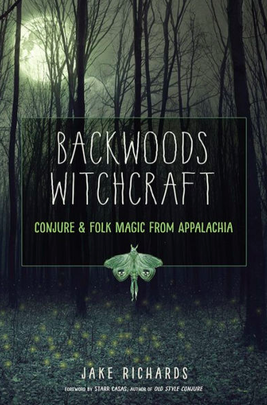

By Amber C. Snider If you’ve ever been curious about the deep magical roots of the American South, look no further than Jake Richard’s book Backwoods Witchcraft. Here, the author recounts family anecdotes, omens, spirit signs, and the remarkable regional folklore of Appalachia.  Jake Richard’s new book Backwoods Witchcraft is not only an exploration of Appalachian culture, but also a deeply moving personal narrative and soulful tribute to the wild mountain terrain of the region. As a geographically isolated population, the ingenious spirit of the Appalachian people has led them to develop not only their own way of life, but also a unique understanding of the spirit world. Here, Richards discusses the power of storytelling in Appalachian culture, including its Baptist roots, and shares practical omens, signs, and a few haunting tales. Amber C. Snider: There aren’t many books out there specifically focused on Appalachian folk magic. I was immediately intrigued when I read that you wouldn't just rehash variations of Wicca. Because Appalachian folk magic is really a hybrid of several traditions (specifically Scottish, Irish, German and Cherokee) that span across multiple time periods and geographical locations, how would you sum it up as a whole for our readers? Jake Richards: That's a big question. I think through the history and oppressions of the Appalachian region that this tradition has become an entity of its own. It’s so distilled with the independent spirit that pervades Appalachian culture. It can be compared to our immigrant ancestors, but it is still very distinct and unique to the region. ACS: By independent spirit, are you also referring to the fact that the Appalachian people – as people of the Earth, of the soil – had to use what was available to them? JR: Exactly. Appalachia was so isolated for so long, especially from the rest of the country as well as the general outside world. Everything took on its own distinct flavor or form, whether it be our religion and the way we practice our spirituality to our economics and our general cultural home life. ACS: What is one distinct feature that makes it particularly unique from the rest of the States? JR: A lot of times, back in the day, we didn't have a church built up so there was a circuit rider (preachers who would travel around from community to community and stay there for about a week preaching the Gospel). Not having a preacher nearby to do marriages or baptisms removed the middle man between the normal folk and God. That's why there's never been really a hierarchy here. It’s similar to the independent spirit that was grown because we did everything else by ourselves. We had to. God became as close as our next breath. ACS: You write about how this folk magic uses the Bible not only as a family heirloom (to record births and keep hair clippings) and sacred household text, but also as a magical resource. Can you tell me a little bit more about this lack of concrete separation between folk magic and modern day Christianity? JR: The bible was mostly used because that was the majority faith here. Everybody points out that the Bible condemns witchcraft or divination, but going back to the independent spirit in Appalachia, what you do here is your business – it's between you and God. So if we take it biblically, magic has never been divorced from mankind at any time in history. It's evident that what the Egyptians did, the Israelites also did magically. We see it throughout the Bible: Moses parting the seas, Jesus cursing the fig tree, people of the temple casting lots to see which heifer God would prefer, etc. The only distinction was that the Egyptians' magic and religion was considered 'evil' because anything that was 'other' or unknown was evil. So my realization was that the people of Appalachia (as well as the general attitude about witchcraft in modern times) have always relied on the communal attitude. ACS: What do you mean by communal attitude? JR: In certain communities you would have folk healers and conjure men and the community would look good upon them because their powers came from God. But there were also 'evil witches,' like Witch Magal down in Gatlinburg who was supposed to consult with the Devil. I've received a lot of [kickback for the book’s title] because the word 'witchcraft' in Appalachia has always been so taboo. But coming from a family that does this work, there's really no distinction between witchcraft or whatever is accepted by the community – whether it's folk healing or conjure work. In my family, we never really made a distinction. That's why there's never been really a hierarchy here. It’s similar to the independent spirit that was grown because we did everything else by ourselves. God became as close as our next breath. ACS: Why do you think there is a reluctance to call it witchcraft? Do you think that that's something particular in the culture or with the word it itself? JR: Witchcraft has always been taboo because anybody who practiced witchcraft was supposed to have gotten their power from the Devil, or selling their soul, or some other deal that they had. But in all reality, what they were doing in the stories can be connected to the same thing conjure healers or folk healers were doing. It's all based on the attitude of the community from eyes of the beholder. ACS: Also the power of storytelling, yes? JR: One of the biggest Appalachian traditions still today is storytelling. I think a lot of the old witchcraft stories can't really be relied upon for finding formulas because 90% of the time they're exaggerated than what actually occurred. ACS: You talk a lot about God in the book. You say that for the people of Appalachia, God is not this figure in the sky, but more like a father figure at the table. He's just part of the community. Can you talk a little bit about that? JR: Essentially we were isolated for so long we had to make do with what we were given on the land. We didn't really have the option to leave because trains back then would only come every couple weeks or every couple of months – especially the trains that went from like the deep South to far up North wouldn't even really stop here. All you really had in little mountain communities was yourself, your family, your neighbors and God. God became a large part of people's daily lives. God played a large role in the folk healing practices here because doctors were scarce. We didn't actually start getting licensed medical doctors until the beginning of the 1900s. And even then that was only one type of doctor. ACS: What other types of doctors were there? JR: There were three types of doctors: those who actually went to school and got their license. And then there were those who were 'book learned' who simply read a lot of medical texts and were self-taught. And then there were the other doctors who were folk healers or those who used herbal remedies. Even today, there's a big suspicion against [modern medicine] and it's not really seen as reliable here. People still do folk remedies and take certain herbs – even against the doctor's wishes. The only difference between what was certain and uncertain was God. So they’d pray for healing or a speedy recovery. But it also crossed other areas of life: praying to find love or a good marriage and with many kids. That's really all you had to get out of life because that's all life really offered. And so God became a familiar figure. A lot more familiar than people would account for him in other places in the world. My Aunt Marie simply called him "Papa." She didn't call on God or Lord or Jesus. And a lot of people still do that. ACS: You also bring up the Devil a lot in the book as a kind of trickster character and in conjunction to "getting him out" or ways to circumvent him. Can you talk a little bit about this idea? JR: Since Appalachian Christianity took on its own certain flavor here, the Devil also went from being this tyrant, all-powerful evil spirit to more like a trickster. Appalachian folk tales are filled with the Devil being outsmarted or tricked himself, so he kind of became a local resident in the folklore. He went from being a “Father of All Lies” to assembling tricks for the spirit that lives at the crossroads. He’s kind of like a black jack dealer that nobody really wants to deal with unless they have to, more or less. Especially in Appalachian folklore, he simply brings bad luck or he tries tricking people but then they just trick him right back. If you compare it with other European folklore stories of evil spirits, he takes on those same traits – whether it's being obsessed with counting things like words, letters, grains, or sesame seeds, as well as not necessarily thinking things through. I've always grown up in the woods and in the creeks, playing with bugs and animals – there's never been a disconnection between me and nature. ACS: Can you give me an example of that in your family folklore? JR: I can't remember if I included this story in the book or not, but it was one that my grandmother told me. My Mamaw Hope has lived up in North Carolina and her husband was a real bad drunk. He apparently always told this story saying that it happened to a friend, but she thinks it really happened to him because his situation was too similar. The story goes that one of his ‘friend’ always went down to a tavern down the road – down the mountain – to get drunk. Well then one night he was apparently walking back and he heard footsteps behind him. And he turned around and there was nothing there. So he kept on walking. But then he heard footsteps and chains dragging on the ground. He turned around again and there was nothing there. So he kept on walking and heard something running up behind him. And he turned around again and still there was nothing there. Well there was a big boulder just off the walking path in the mountains and when he turned back around there was a shadow on the rock. It jumped down and tackled him to the ground, so he started wrestling with the [thing] and chains were smacking around everywhere. He never really got a good look at the shadow or whatever it was, but it simply whispered in his ear, ‘You start being being good to your wife and kid, otherwise I'll come back and drag you down to hell.’ ACS: Oh wow, that’s quite the story...and then what happened? JR: The shadow thing just disappeared. Apparently the ‘friend’ went back out the next day to see that there were, indeed, prints of chains where they had smacked the ground – as well as cloven footprints. The story goes that it was the devil himself tackling the old drunk and telling him to be nice to his wife and kids. But the friend, of course, was never identified 'cause we're pretty sure it actually happened to Papaw. ACS: You also you talk a lot about Cherokee traditions and your Native American ancestry. In one section of the book, you mention the mysterious Moon-Eyed People. Who are they and where did they come from? JR: There are multiple speculations about who the Moon-Eyed people were. They're often described as being light or pale skinned with blonde, brown hair and big blue eyes. The story goes that the Cherokees had to run them out West, but no one really knows where they came from or exactly who they were. They apparently spoke a different language when the colonizers came upon them, but I read that they spoke English, too. They had different, distinct facial features, but not many people know about them anymore. They could be a section of a tribe that was here before the Cherokees and other Iroquois started moving down here from the Great Lakes. ACS: In the book you mention that after your Papaw Trivett passed that white feathers kept showing up and you could smell his spicy cologne. What are other signs that spirits are trying to connect or communicate with us? What should we pay attention to? JR: My family has always paid attention to our dreams. If you see one of your deceased relatives in a dream, especially just after their passing, we always pay attention to what they're doing in the dream. If they're running around frantically or if they're scared or angry then that means their spirit [is not at peace]. But if they're calm and collected that means that they are at peace and they are simply letting you know that they are okay. My grandmother still has a bag full of pennies that my Papaw Trivett's spirit left going from her front door to the passenger side of her car – just simply laid out one by one in a row. We also used to have this box filled with all these white feathers that we found around the house one day [after he passed away]. ACS: The pennies and feathers just showed up out of nowhere? JR: In my family, we always try and rationalize something before we accept it as a spiritual sign and we could not figure out for the life of us why somebody would just do that. I still find feathers and I don't own anything that has feathers in it. I have jars with bird feathers around but those are from crows and blue jays. But these are little white goose down feathers that you'd find in a pillow or bed. I'll still find them places – like I'll sometimes be driving and the windows are rolled down and one will fly right into my car and just circulate or drop to the floorboard. Spirits can communicate with the living in a multitude of ways. It’s not like there are definite signs or anything like that. I've known people who get signs from their ancestors or their deceased relatives through yellow mark butterflies or certain birds. There's one bird – it's a deep cobalt blue bird with an orange chest, kind of like a robin. ACS: Yes, I've seen them. I tried to find the name of that bird too because it came to my window right after my aunt passed away... JR: Those birds and the broad red cardinals and sometimes the yellow finches are used a lot for spiritual messages from the dead in Appalachia. We take them as messages from spirits, as well finding feathers laid out weirdly. It also happened to my grandmother on my dad's side of the family. When my Papa John passed, she found three, white down feathers in her fridge and had no idea how they got there. Spirits can communicate with the living in a multitude of ways. It’s not like there are definite signs or anything like that. I've known people who get signs from their ancestors or their deceased relatives through yellow mark butterflies or certain birds. ACS: What are some other signs of good omen or good luck? JR: The yellow finch is considered to be good luck and obviously finding a penny on heads instead of tails. Whenever we found a spider nesting or laying a web in the kitchen we always left it because it was a sign that the house would never go hungry or the cabinets would never be bare. If you see trails of ants in your house and they don't really have a directive or if they're not really going anywhere (like they're just crawling all over the place) – that's a sign that somebody in the house was restless, like their mind isn't right or they're uneasy or just not wanting to be there. That especially happens a lot during big life decisions and big life stages. I've seen that happen a lot with houses that have teenagers in them. ACS: What led you to put together this hybrid collection of family history and folklore and Appalachian culture? JR: Honestly, I don't remember deciding to write the book. I think my spirit simply led me to do it because the next thing I knew I had a table of contents laid out. I was also getting tired about all the misinformation online about what Appalachian folk magic really is. Most of the time, everything that I had seen online came from people who simply say that their grandparents are from here, so it’s really just a bunch of outsiders. And some of the books that have been written on this subject were simply too mixed up with modern magic and modern techniques. So I finally just said, you know, screw it. You gonna write about it, you gonna write about it! The entire process was directed by the spirits. Even while I was writing the book, I was remembering things to include: I would have dreams of my ancestors coming to me saying, 'Don't put that in there just yet. Don't forget to talk about this...' I'm glad that's over 'cause I don't think I had one night of sleep with a normal dream! I was like 'Damn y'all get off my ass!' ACS: What was the community's reaction to the book? JR: I haven't really had any resistance when it comes to people here with the work, but sometimes they do get a bit confused and a bit paranoid. ACS: Paranoid, how so? As in, it will bring too much attention to the community? JR: Well there's also the taboo against witchcraft. They are a bit suspicious as to exactly who is really in control. Just recently I was in Lee County, Virginia to help a little older woman in her 60s with a haunting in her house. The entire time I was cleansing the house, she was constantly asking questions – which I get that's a normal thing, 'cause it's not really normalized anymore. But she just had this feeling about her that she didn't really trust me. She'd be like, 'What are you saying? Are you praying? What are you doing?' But then by the end, she felt so much better. I mean, this woman's house had been haunted so bad to the point to where she hadn't left her house since last November. And by the time me and a couple of other colleagues were done cleansing the house, she was actually able to leave. Her five friends took her down to her Aunt's grave because she hadn't been able to go down there because she had been stuck in the house. [Afterwards] she was a totally different woman than the one that I had met about four or five hours prior. ACS: So she more relaxed and calm and confident after you performed the ritual? JR: Oh definitely. When we first met her, this woman is a nervous wreck 'cause she hadn't been able to get any sleep. Her kids initially brought it to her attention saying, 'That mean old witch spirit keeps pinching our toes until they bleed.' There was also a big sinkhole that had appeared on the property and one of the kids (while sleepwalking) kept being led to that sinkhole. So I can understand why that would've been nerve wracking. She just had this demeanor of defeat, like a dog tied up. ACS: Any chance for a second book? JR: The second book has already started, but before we start heading down that road, I want to see if the world is ready and if the people of Appalachia today are ready. To read more about Appalachian culture, check out Jake Richard's premiere book Backwoods Witchcraft on sale at Enchantments or online here.

2 Comments

Julia Thompson

7/3/2022 06:00:41 am

Would the author be available to speak in my community? Perhaps a discussion format or a workshop? Thanks

Reply

Anonymous

9/29/2023 06:04:50 pm

@jandu_thegifted_doctor on Instagram, her spell works are very effective

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

April 2024

MastheadPublisher Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed